Why We Should Know about the Basic Needs of the Middle School Brain

At some point in their careers, ask any middle school teacher and they will most likely have heard the following from their students: “When did we learn this?”, “Wait – there was homework?” or “Do we need to know this for the test?”

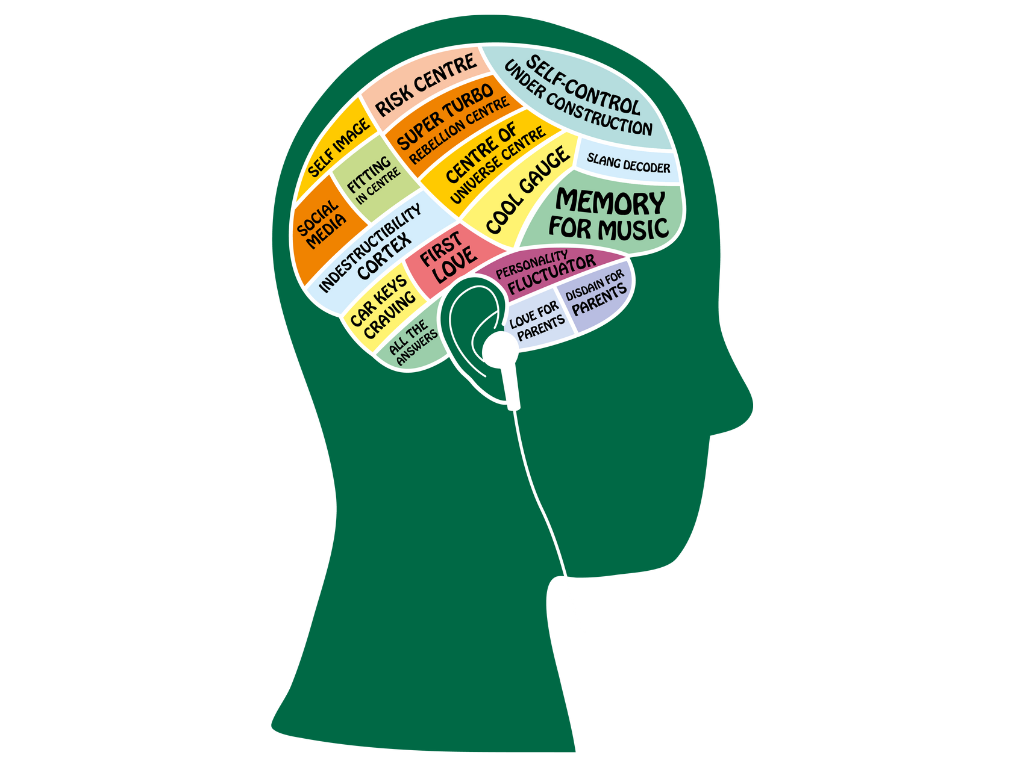

All of these questions may come across as frustrating, especially when you swear you have been clear with what you have taught, discussed, debated, and reviewed just as much as a drill sergeant. But some students can enter and exit the class with little retention or awareness of the actual content and concepts of a lesson. One of the reasons? As middle schoolers are developing socially, emotionally, and physically, so are their brains. And if teenage brains are not engaged and stimulated sufficiently, they hit delete (otherwise known as pruning) in their heads. They may forget information due to lack of relevance, lose track of requirements as they transition from class to class, or selectively choose to remember information, depending on interest, value or importance. A lot is happening in middle schoolers’ heads so wouldn’t it be wise to pay attention to the noise and necessities of these learners?

Typically in middle school, teachers have been trained in (or learned by experience) the importance of classroom management, differentiation, and the need for varied assessment. However, studying the teenage brain and what its needs may be for effective and meaningful learning is often overlooked. This is a disservice to both educators and students since during middle school, these distinct years are marked by rapid and extensive brain development that should not be ignored.

The middle school years have substantial implications for learning needs and to optimally facilitate this growth, schools should examine their curriculum to see how much of it is catered to the unique neurodevelopmental changes for teenagers. One model— The International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC)—centers and structures learning around the adolescent brain’s needs. The curriculum has been researched and designed to meet the needs of learners, and in turn, their well-being, by identifying six key needs of the teenage brain. These needs are known by an acronym known as IMPART: Interlinking learning, Making meaning, Peers, Agency, Risk-taking, and Transition.

Interlinking learning, the first need, is pivotal in the teenage brain’s cognitive functioning and long-term memory retention. Neuroscientific research reveals that the brain learns through an ‘associative’ process—making connections between brain cells and interlinking new information with previously stored data (Buonomano, 2012). A curriculum, such as the IMYC, can address this by weaving conceptual connections, known as Big Ideas, throughout the learning journey. As students move from subject to subject and lesson to lesson, the Big Idea serves as a connector among concepts, promoting deeper understanding and more lasting knowledge. It encourages students to identify links across subjects and apply their understanding in an integrated manner. Interlinking learning also helps teachers in middle school to get off their “islands”, starting conversations and creative collaborations between subjects that can often be seen as unrelated.

Importantly, interlinking learning also can foster metacognitive skills, enabling students to become aware of their own learning processes. They become skilled in recognizing patterns, associations, and relationships between different pieces of information, thereby improving their problem-solving abilities and creativity.

Next, making meaning is crucial, as the adolescent brain undergoes a ‘pruning’ process, potentially losing less-utilized connections. This neurological process eliminates weaker synaptic connections while strengthening others, thereby enhancing the brain’s efficiency. However, it also poses the risk of important connections being lost if they are not regularly utilized or if they lack significance for the learner (Geake, 2009). Meaningful learning helps students retain important connections and promotes cognitive efficiency. When a curriculum focuses on real-world application and experiential learning, this supports students in making meaningful connections with their learning experiences.

Understanding this, the curriculum should focus on making meaning by creating learning experiences that are relevant, engaging, and applicable to real-world contexts. It should encourage students to relate their learning to personal experiences, societal issues, and global challenges, thereby attributing personal and societal significance to the knowledge.

Another need—peers—plays a fundamental role in teenage brain development. Neuroscientists have found that during adolescence, the brain’s reward systems are highly responsive to peer interactions, and these interactions significantly influence both the reward system and decision-making processes (Crone & Dahl, 2012). Peers become an important aspect of the learning environment, affecting not just the social and emotional aspects of adolescent development, but also influencing academic outcomes and cognitive development.

Peer relationships offer numerous benefits for learning during these formative years. Collaboration and cooperation within peer groups foster a sense of community and shared purpose, promoting positive attitudes towards learning. They also provide opportunities for social learning, where students can observe, imitate, and learn from their peers’ behaviours, strategies, and perspectives. Furthermore, peer interaction encourages communication, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills as students learn to navigate diverse opinions, work towards common goals, and resolve conflicts. It also provides a platform for feedback, with peer assessment often seen as a valuable tool for promoting reflective learning and self-improvement.

Along with the role of peers, learner agency involves providing students with opportunities to make decisions, take responsibility for their learning, and experience the consequences of their actions. This can be achieved through methods such as project-based learning, student-led discussions, and self-evaluation activities, all of which encourage students to take ownership of their learning. By encouraging agency among learners, educators are fostering their autonomy and resilience.

Agency also promotes self-efficacy or the belief in one’s ability to succeed in specific situations or accomplish a task. Students with high self-efficacy are more likely to embrace challenging tasks, persist in the face of difficulties, and recover more swiftly from setbacks. They are also more likely to engage deeply in learning activities, seeking to understand and master the subject rather than merely achieving good grades.

Risk-taking, while often viewed negatively, is an essential aspect of adolescent development. Adolescents are hardwired to value the rewards of risk over its potential downsides, particularly when social factors are involved (Steinberg, 2008). Adolescence is a time of exploration and experimentation, both of which often involve taking risks.

Learning should facilitate safe risk-taking, such as undertaking challenging tasks or presenting in front of peers, which can bolster teenagers’ decision-making skills and resilience. Risk-taking in a learning context can be perceived as the willingness to face uncertainty or potential failure in the pursuit of learning goals. This might include trying new strategies, proposing unique ideas, tackling challenging tasks, or sharing personal perspectives, all of which involve stepping out of comfort zones and potentially facing judgment or failure.

Educators play a crucial role in fostering risk-taking. They can model risk-taking behaviors, celebrate efforts and growth over perfect outcomes, and provide constructive feedback that encourages students to learn from their mistakes. Importantly, they can create a supportive, respectful classroom environment that values diverse perspectives and learning paths, thus making students feel safe to take risks.

The final need in the IMPART model is transition, which refers to the capacity to adapt to change especially with the constant changes and progression that students experience throughout their middle school years. For example, the period of learning during middle school involves various shifts: transitioning between different subjects, classroom environments, educational expectations, or even moving from the exploratory middle school years into the more exam-focused, high-pressure high school phase. When navigated appropriately, transitions can become growth opportunities as students learn to be flexible and accommodate new expectations and environments, while also developing skills to manage stress and challenges.

To help with the transition process, educators can provide explicit instruction on managing changes, create supportive environments where students feel safe to express their concerns and establish clear expectations for the next phase of learning. There should be approaches that provide continuity in learning which focus on transferable skills and knowledge and also promote a sense of community that can provide social support during these transition periods. Additionally, incorporating activities that foster resilience and self-efficacy can empower students to navigate these transitions with confidence.

As more educators learn the needs of the teenage brain, such as the IMPART model from the IMYC, learners and learning align better, ensuring an environment that not only enhances cognitive development but also health and well-being. By placing students at the heart of the curriculum and focusing on their unique needs, educators can help shape adolescents into resilient, responsible, and successful adults.

Learn more about The International Middle Years Curriculum (IMYC) and International Curriculum Association

References

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control.W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

- Buonomano, D. (2012). Brain Bugs: How the Brain’s Flaws Shape Our Lives. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN: 0393342227

- Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(9), 636-650.

- Geake, J. (2009). The Brain at School: Educational Neuroscience in the Classroom. Open University Press.

- Steinberg, L. (2008). A Social Neuroscience Perspective on Adolescent Risk-Taking. Developmental Review, 28(1), 78-106. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002

I am currently a college student trying to pursue a degree in teaching. This semester I learned the importance of knowing that middle school students are going through many developmental stages in their lives. To the students, there are more important things going on than school. They will forget to do their homework or may not want to pay attention to the lecture. As teachers, it is our job to make sure that we are meeting the needs of the students so they are able to focus on their school work. Peer interaction is a big part of an adolescent’s life, so the more social interaction you give to the students the better. This can come in many forms too, having them do group work or group discussion can give them the social interaction they need.