Think about the Common Core State Standards as an ambitious remodeling project happening all over the country. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have adopted new shared goals for what their students should know and be able to do in literacy, and middle grades schools all across the country are figuring out how to bring instruction “up to code.”

Will schools take a “pre-fab” approach to the remodel, dropping in off-the-shelf components and hoping they will fit and function? Or will they take a custom approach, relying on the skilled craftspeople on the front lines of instruction to make adaptations to suit the needs and contexts of their schools?

Exciting new survey results from the National Center on Literacy Education (NCLE) demonstrate the power of the custom approach, and in particular the power of teacher collaboration, in driving Common Core State Standards (CCSS) implementation.

The survey was conducted online in October 2013 among members of organizations in the NCLE coalition (which includes AMLE) and garnered responses from almost 5,700 K–12 educators, including more than 3,000 classroom teachers (nearly 900 in middle grades schools). The survey was limited to respondents in states and roles actively implementing the CCSS in ELA/Literacy.

Successful Transitions to CCSS

The transition to the CCSS seems to be most successful when teachers are highly engaged in the process and have time to collaborate to leverage their collective professional expertise to bring all students to higher levels of literacy. This is great news for middle grades schools, where teaming structures provide a framework for doing the kinds of interdisciplinary work called for by the CCSS.

The nearly 900 middle grades teachers who responded to our survey reported a wide variation in how their schools are approaching the change, but send four clear messages for making the transition a success:

1. Accelerate the changes by keeping front-line educators engaged in designing how literacy skills can be taught differently.

Middle grades schools across the country are taking a range of different approaches, some dependent on purchased materials, some much more teacher-driven.

We asked middle grades teachers how engaged they are in several aspects of the CCSS transition. Is this a change they are driving, or a change that is being done “to” them? We discovered that three specific kinds of teacher engagement are crucial to how well the CCSS transition is going:

- Planning how their school will implement the standards.

- Having time with colleagues to work on the standards.

- Identifying and/or creating their own materials and approaches.

From having a voice in planning how their school would implement the standards, to having time with colleagues to dig into the meaning of the standards and implications for classroom practice, to being trusted to exercise their professional judgment in terms of what materials will best help their particular students reach the standards, engaged teachers are making more progress at every step of CCSS implementation: supporting the standards, feeling well-prepared to help students meet the standards, and actually making changes in their classrooms.

2. Make collaboration time purposeful professional work by focusing on real instructional tasks.

One of the most powerful predictors of progress with implementing the standards was teachers having time to work through them with colleagues. Middle grades teachers have an advantage here compared to teachers at other levels, reporting more built-in time for team work than elementary school or secondary school teachers.

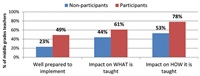

Compared to teachers who are doing it on their own, teachers who participated in collaborative work with colleagues around the standards were twice as likely to rate themselves as well-prepared to help their students meet the standards and also much more likely to report having already made moderate or significant changes in their teaching in response to CCSS goals.

Table 1. Participants who collaborate around standards are better-prepared and make bigger changes.

Table 1 illustrates the impact of collaboration on CCSS implementation, showing that teachers who have opportunities to collaborate around the standards report being better prepared to implement the standards and are already making more changes in their practice. Clearly, with fewer than half the teachers who responded feeling well-prepared, we are at an early stage in this transition. Providing time for teachers to work through the standards together is one of the most powerful ways to raise the level of preparedness.

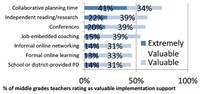

Table 2. Middle grades teachers rate collaboration as the most valuable support for CCSS implementation.

Middle schools across the country are investing huge amounts of time and money in professional learning around the new standards. But what kinds of learning experiences do teachers tell us really make a difference in their ability to implement the standards? As Table 2 illustrates, among middle grades teachers in the NCLE survey, hands-on planning time with colleagues was the clear winner.

The survey also provides a window into what teachers do during that time that makes a difference for student learning. Teachers who reported that they frequently engaged in the following CCSS-related tasks with a collaborative team were making the most progress:

- Co-creating lessons

- Co-creating assessments

- Examining student work together.

For example, teachers who reported that they frequently had the opportunity to spend time with a team looking at real examples of student work relative to specific standards were twice as likely to rate themselves well-prepared to help their students meet the standards.

Research suggests that this relationship is so strong because professional learning that is embedded in the real work of instruction is far more likely to lead to desired changes. Such tasks let teachers pool their insights and experiences and adjust their practice in real time. Investing in the time to do this kind of practical, applied work will pay off in remodeled instruction that is more coherent and structurally sound.

3. Bring educators in all disciplines and roles together in shifting literacy practices.

Middle grades teachers have always understood that literacy is central to student success across the curriculum. In the 2012 NCLE survey, 80% of middle grades educators in all job roles and subject areas agreed that “Developing students’ literacy is one of the most important parts of my job.”

The Common Core builds on that existing shared ownership of literacy development by providing a structure of common goals, a more concrete description of what it means to be literate in the 21st century that educators can work toward together.

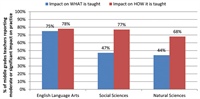

Table 3. Middle grades teachers across subject areas are shifting literacy practice.

Our data show that middle grades teachers across subject areas are shifting practices in response (see Table 3). Majorities of teachers across subject areas report shifts, but teachers of natural and social sciences were more likely to report an impact on how they teach than on what, suggesting they are getting the message that CCSS are not asking everyone to become English teachers, but rather to be more conscious of and strategic about literacy development within their own content area.

4. Build teacher ownership of the change by providing space and support for them to innovate and design the lessons and materials that are right for their students to meet the CCSS goals.

Some of the most striking findings in our survey have to do with the role of textbooks and other materials in the transition to CCSS. When asked if the “main curricular materials” (presumably textbooks) they were currently using are well aligned with the new standards, 59% of middle grades teachers say they are not. Under a model of educational change driven by teachers sticking to a script, this would be a problem, the assumption being that without an aligned textbook to follow, teachers will not shift their literacy practices in the desired direction. In fact, just 25% of teachers rated finding instructional materials aligned with the standards to be a major challenge.

It seems that teachers have a much broader definition of materials than purchased textbooks. As envisioned in the standards document, teachers are drawing on a wide array of resources from classroom libraries to newspaper and magazine articles and especially lessons designed by other teachers near and far. The transition to the new standards coupled with digitally literate teachers has led to an explosion of sharing and adapting of instructional materials, some on education-specific platforms but many more through the use of broader technologies such as YouTube, Pinterest, and Twitter.

Last fall, almost 90% of middle grades teachers reported that in their district, teachers are identifying and/or creating their own materials and approaches to meet the standards. This is exciting news: sustainable change comes from the bottom up, powered by the insight and ownership of those on the front lines.

A Teacher-Powered Transition

Data from the 2013 NCLE survey suggest that most middle schools are taking a “custom” approach to this huge remodeling job, drawing on the talents of teachers to bring the general code of the CCSS to life in ways that make sense in their specific context.

District and school leaders can continue to support a successful, teacher-powered transition by:

- Involving teachers in planning for the change.

- Protecting time for teachers to collaborate on standards implementation.

- Focusing collaboration time close to the classroom: on designing, testing, and revising lessons and assessments.

- Keeping the collaboration interdisciplinary.

They can also give networked teachers the autonomy to create and design the materials that will get their students to the shared goals of the standards.

Catherine Awsumb Nelson is an evaluation and research consultant for the National Center for Literacy Education. catawsumb@gmail.com

This article was published in AMLE magazine, March 2014.

Think about the Common Core State Standards as an ambitious remodeling project happening all over the country. Forty-six states and the District of Columbia have adopted new shared goals for what their students should know and be able to do in literacy, and middle grades schools all across the country are figuring out how to bring instruction “up to code.”

It is evident that standards are not “up to code.,” but it is not for a lack of trying. Schools across the country are trying everything thing they can to improve literacy in the educational system.

I agree with Ms. Nelson. For teachers to succeed they need to be engaged in the process of planning how their school will implement the standards, have time with colleagues to work on the standards, and create their own materials and approaches. A lot of time, energy, and money have been spent on restoring literacy, but the journey is far from over. Perhaps with greater collaboration amongst teachers of all disciplines, the pace of the journey will quicken and the time it takes to level the field will decrease.

I also agree that it is going to take a lot of support in order to give our students exactly what they need collectively and individually to succeed.

Buddy Robinson

6th Grade ELA

Summitt View Academy