Effective test prep means understanding the test as well as the content.

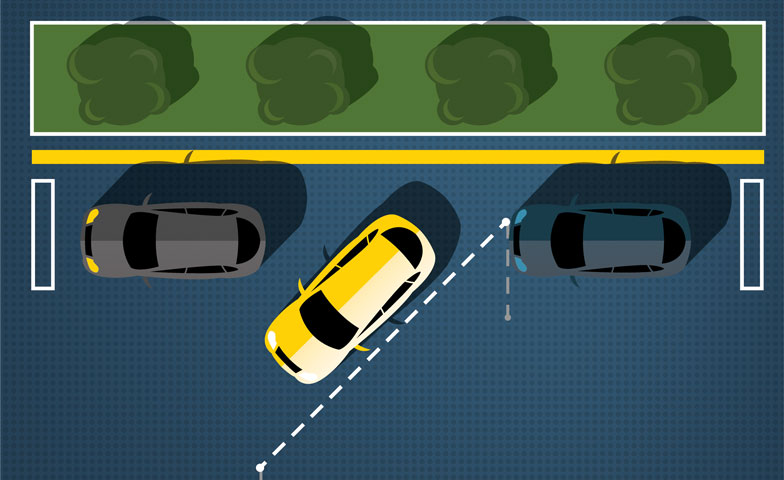

This is a practice question on the New York State DMV website for the written portion of the driving test. Unfortunately, despite a stellar driving record and an obsession with never paying for parking, I missed this question. Why? I decided to attempt the test without studying, without previewing the format or brushing up on the language used in the handbook. I wanted to put my favorite GPS analogy about test-taking to its own test.

I tell my students there’s no need to worry about state assessments because through our learning experiences, I’m teaching them what they need to know. However, when March rolls around (the New York state assessment is given in April), I do spend a few weeks practicing the assessment with students. The plan is not to “teach” them anything at that point, but rather to familiarize them with the format of the test.

I’ve implored my students for years to think of it like this: No matter how much you practice driving, you need to study the manual to understand what will appear on the written portion of a driving test. Why? Because, no matter how prepared you are, if you aren’t acquainted with the format of the test, conversant in the types of language and graphics that are used, and accustomed to the layout of the test, you might not pass. Even if you are an excellent driver, the test stands in the way of your ultimate success.

Choosing the Route

Let’s view a school year as a journey. Teachers plan the trip, ultimate destination in mind. In a sense, our lesson plans are the itinerary and the curriculum our maps. Each road we take has an impact on the final destination.

Let’s view a school year as a journey. Teachers plan the trip, ultimate destination in mind. In a sense, our lesson plans are the itinerary and the curriculum our maps. Each road we take has an impact on the final destination.

Maybe you are a teacher who prefers the scenic route with plenty of opportunities for improvisation or “off the beaten path” experiences. You probably have a colleague whose trip looks significantly different than yours because he never veers off the highway, sticking closely to the map. Arguably, both philosophies have merit—and they both have the same final destination.

The journey my project-based learning classroom takes, no matter how much I anticipate roadblocks and dead ends, sometimes veers off in the wrong direction and we have to double back. Now, to me, that is part of the beauty of a road trip—the unexpected starts and stops often are the most memorable moments when valuable lessons are learned. My students are often in the “driver’s seat,” allowing me to enjoy the view. This instills confidence in them that they are in charge of their own learning and are co-creators of their learning experience.

Yet, I have a teacher friend whose meticulous attention to the most efficient (and maybe most effective) route consistently takes his students directly to our shared destination—always ahead of me. He is a connoisseur of best practices and “most bang for your buck” activities, and directs his students on their way to success with little freedom of choice. Clearly, he is driving the bus, and many students find great comfort in his direct route.

It’s easy to see how my friend’s students arrive at the final destination—they don’t take side trips. But how do my students “get there” and arrive prepared for an assessment that I barely mention? Until recently, I’d be hard-pressed to convey clearly how this happens. It’s like knowing how to get somewhere but not knowing the names of the roads or how many lights until the next turn.

Thinking About Their Thinking

The more times I make the journey, the more I observe about the experience. What I’ve noticed is that project-based learning requires and encourages students to think about their own thinking, and I’ve translated these metacognitive experiences into academic skills that help students succeed on the assessment. I call it their “metacognitive training.”

This isn’t nearly as fancy as it sounds, but it has proven to be a successful component of my classroom and, as it turns out, an essential skill for analyzing author’s purpose and answering multiple-choice questions as well. It works like this:

When I ask students a question, I allow them to answer, then I ask, “What makes you think that?” Their answer to the second question is more telling than whether they got the right answer. Once I make students aware of their own thought process, essentially having them retrace their steps, they can usually see how they arrived at the correct answer or realize how they swerved off to an incorrect one.

This is an effective way to teach students to use details in their writing and to elaborate. Ultimately, when they are able to think about their own thinking, they are able to draw evidence from texts as well because they can now understand what it means to ask “Why do you think that’s what the author meant? What was her thought process?” This has revolutionized my approach to teaching author’s craft and structure because I can help them appreciate that what they read was constructed and can be deconstructed, just like their answers.

Metacognition is equally advantageous for multiple-choice questions. Instead of relying on the test itself to provide possible answers, I teach students to “get it in their head” before reading the answers. The answers are created by test makers who admittedly use distractors to flesh out what students know. I’ve worked on state test development a number of times and when I explain the item-development process to my students, they understand why they should trust themselves over the answers provided.

I tell them to cover the possible answers with their hands—to not even skim them—because their brains will try to find the answer while the test itself often tries to obscure it. Once they have the answer in their head, they are then reading the answers to find the one that most closely matches theirs.

Knowing How to Drive

As my caravan of learners approaches this year’s assessment, I remind them that we’ve been learning together how to investigate the best direction in which to move, to trust our educated instincts, and to think about our own thinking. The learning experiences I designed for them, and some they discovered on their own, were informed by the Common Core Learning Standards. Yet, to be fair, I remind them that knowing how to drive requires they pass a written test that measures what seems impossible—how well they would actually perform as a driver.

Why did I miss the parallel parking question? Is it because I’m a bad driver? No. Missing that question doesn’t prove I’m a bad driver, but if I have to, I can learn how to take the test correctly and prove that I am able to adjust my thinking—a skill all students must master to be successful academically—to be college and career ready.