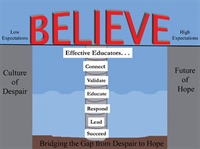

What bridges the gap between a culture of despair and a future of hope for children who live in poverty?

The answer is simple: effective educators who will not settle for mediocrity, who will not accept excuses for why these children can’t learn, who are willing to do whatever it takes to help each child succeed, who establish supportive environments where children learn to bounce back from life’s negative circumstances and thrive.

Many Americans believe that low-socioeconomic level equals low outcomes. This is far from the truth and those who believe otherwise stifle what a child can accomplish. Children who come from generations of poverty or those who find themselves there because of life’s circumstances still dream, have hopes,

and want to achieve.

Poverty does not mean a person is unable to succeed. Children who live in poverty can meet high expectations and standards.

When we as educators understand and embrace this truth, outcomes for children who live in poverty will change.

In a 2012 Huffington Post article, “Good Teachers Create the Future,” Kati Haycock, president of The Education Trust, states: “Good teachers—and counselors and social workers and school principals—matter. They matter a lot to kids of all sorts. But they especially matter to kids of color and kids who are growing up in poverty.”

Too often the consequences of poverty eat away at what children can do academically. Yet, there is still hope. Hope lies in what educators do between the first and the last bell of each school day to equip children with the necessary skills to catch up, move forward, and succeed in the 21st century.

Effective educators of children who live in poverty understand the important role of connecting, validating, educating, responding, leading, and succeeding with children who live in these environments.

As a child of poverty who dispelled the assumptions that low-socioeconomic levels equal low outcomes, I dedicate my life to educating children who come from environments where the norm is lack rather than plenty. In my journey to lead children of poverty, I have formulated six effective practices.

Connecting and Validating

Everything that takes place in a school is built on relationships and validation. Building relationships is often considered a “soft” principle and is overlooked when devising strategies to educate children who live in poverty. However, effective educators know building relationships is a critical step before introducing content.

Students connect and build relationships with individuals before they connect with an institution. Johns Hopkins University Professor Robert W. Blum contends that lasting, meaningful relationships with at least one caring adult in the school are the cornerstone of connectedness.

Hand in hand with connecting is validating. Validating means understanding where the student is coming from and not allowing this knowledge to deter a commitment to teaching that student. The focus is shifted from what a student doesn’t have or know to what that student has and can do. Furthermore, it means listening to a student verbally and nonverbally.

After a relationship has been established, the attention moves to believing. Effective educators believe that these students can be successful. Believing in someone causes effective educators to respond in a different way.

The masterful facilitators of learning understand that “Caring is nurturing; believing is strengthening. Caring is validating; believing is promising. Caring is responding; believing is empowering (from “Unmasking the Truth: Teaching Diverse Student Populations,” Middle Matters, February 2006).

Seven ways to connect to and validate children who live in poverty:

- Establish a caring and believing environment.

- Get to know each student’s name.

- Determine what each student is interested in.

- Survey students to learn about family and daily practices.

- Identify students’ learning styles.

- Allow students to “tell” their story.

- Build lessons based on information learned about the students in your class.

Educating and Responding

If children who live in poverty are ever going to have a chance to move forward in life, we must ensure experienced teachers who are highly qualified stand at the door of each classroom. This is the only way to guarantee students will be met at their current level and prepared to move to higher levels.

Effective educators of children who live in poverty acknowledge challenges that are often not experienced when working with other groups. Children who live in these environments struggle with language, reading, writing, and mathematical skills. These children often do not grow up in environments where they are exposed to doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, teachers, accountants, or professions that call for more advanced skills and degrees.

The only part of a child’s life that an educator can control is in the school and in each classroom. What happens there often determines success or failure for these children. Classrooms where children who live in poverty can soar are welcoming and inviting and structured. Instruction is engaging and culturally responsive. Data are constantly used to inform instructional changes. Each student is given multiple opportunities to succeed and is allowed to demonstrate mastery through learning style or intelligence.

Educators can take steps to identify those who show early warning signs of struggling with instructional material. The appropriate response depends on the need of each child and the understanding that one size does not fit all. Responding includes ensuring time is built into the school day to teach, reteach, and advance instruction. These forms of interventions contribute to the success of each child.

Seven ways to educate and respond to children who live in poverty:

- Teach with confidence.

- Establish high, consistent expectations and practices.

- Make reading the default curriculum.

- Use data to inform instructional changes.

- Restructure time and space for more flexibility in responding.

- Create student-centered and culturally responsive lessons.

- Use multiple ways to keep students actively engaged throughout the teaching and learning process.

Leading and Succeeding

As district, building, and classroom leaders, we set the tone for educating children who live in poverty. If we accept ineffective instruction, we can expect low outcomes. If a culture of low expectations and despair is accepted, students will never rise above mediocrity.

On the other hand, if effective instruction is the norm, the result is positive outcomes. If every child is taught to his or her strengths, every child will perform and master content at higher levels. If high expectations and hope are accepted, children will be prepared to be successful in school, life, college, and career. If children are cared for and believed in, they will learn to be resilient. If instructional time is masterfully facilitated, students will rise above what is expected.

Seven ways to lead and succeed with children who live in poverty:

- Establish an environment where every child is accepted and nothing less than the best is tolerated.

- Find the positive in every child and every situation.

- Provide opportunities for educators to learn more about children who live in poverty.

- Eliminate practices that limit or hinder student success.

- Change what does not work and incorporate strategies and practices that support achievement.

- Measure and report progress frequently.

- Work collaboratively to develop the best environment for children.

From Despair to Hope

Poverty cannot be used as an excuse to educate students ineffectively. Children who live in poverty face challenges and circumstances that impede their understanding and learning. Although poverty may hinder the educational process, it does not sentence children to a life of failure nor does it cancel out opportunities to succeed.

According to Kati Haycock (Education Watch: Minnesota, 2006) “Good teachers make good schools. Students who get several effective teachers in a row will soar no matter what their family backgrounds, while students who have even two ineffective teachers in a row rarely recover.”

Low expectations, ineffective instruction, low level programming, and limiting institutional practices must be eradicated. The crucial focus of 21st century educators must be to continuously find ways to help children who live in poverty build a bridge from a culture of despair to a future of hope.

Cynthia “Mama J” Johnson is the lead middle school principal and project leader for the Kansas City Public Schools. She has been a classroom teacher, administrator, and adjunct professor in urban, suburban, and rural environments for 26 years and is a frequent presenter at AMLE conferences. mamaj@mamaj.org, www.mamaj.org

Published in AMLE Magazine, November/December 2013.