This article is timed to coincide with the celebration of National Comic Book Day, which will occur on Sept. 25th.

Introduction & Rationale – Why create comic books?

When Jason was a middle school student, comics were a contraband medium not only in the classroom, but among friends. Students would not necessarily disclose themselves as active comics readers. Things have changed since then.

Comics can be used in a variety of ways in the classroom from texts for reading to creating. In this post, we highlight some possibilities we have enjoyed with this medium, from reaching across disciplines to include focus on close reading of words and images to composing visual creations. The visual and verbal nature of comics lead to natural opportunities to read and reread – in fact, graphic novelists spend countless hours creating the details of images and many of them hope that readers will revisit panels to take in those layers.

Because of the attention they have garnered in the media and cinema over the past decade, many students are generally familiar with the most popular comic topics. However, librarians have also been essential in amplifying comics outside the superhero genre.

Over the past few decades, we have been rapidly transitioning away from a society based on traditional literacies (reading and writing) to one based on visual, digital, and multimedia literacies. But education has always been slower to change. Bringing print comic books into the classroom (along with the highly popular webtoons) is one way to bridge the gap and embrace the “new.” With a combination of both images and words, comics require higher level thinking and processing of visual and written data – an important skill in today’s image-saturated world.

How To – A Beginner’s Guide:

When it comes to reading comics, we highly recommend sharing texts using a projector or passing around copies of a class set. There is so much in the image-based nature of comics that does not immediately come through in a traditional read aloud. Shared reading is the way to go.

Teachers may also want to think about helping students learn how to read a comic book. The structure and organization of a comic is different from a novel. Helping students understand the parts of a comic book page – panel, frame, speech bubble, gutter – can be quite useful, especially for multilingual students, students new to the genre, and students with dyslexia.

For creating, paper and pencil can be embraced as a way of showing the writing and creating process, from the rough draft of penciling to the revising stages of inking. What is more, students can use sites like Book Creator to bring pages to life and even embed photographs as well as audio recordings for rich and complex works. Book Creator also has comic book page templates, which can be helpful for novice students (and teachers).

Book Creator also offers several sample comics in the “Discover” section of its website that students can look to for inspiration before diving into creating their own. Jason has used Book Creator with elementary and middle grades students in online clinical work, and Megan has made use of this tool in classroom practice.

Case Study – Social Justice Comic Books in Megan’s Classroom

The refrain of comics as “superhero books” is often an assumption that is challenged and expanded by Jason in his conversations with comic creators on his podcast “Words, Images, and Worlds.” Whether it is newspaper comics strips or the contemporary work of creators like Jerry Craft and Raina Telgemeier, comics do much more than tell superhero stories. Superhero narratives are, of course, enjoyable for some readers, but it is important to note that comics are a medium, not just a genre.

The storylines of characters like Sam Wilson/Captain America contain a variety of social justice themes, as does work by authors like Nate Powell, Andrew Aydin, Kayla Miller, and more. Students in middle grades have a burgeoning sense of justice and a curiosity about the world. Therefore, books like the ones by the authors mentioned above can be meaningful sparks for thinking about (and doing) activism.

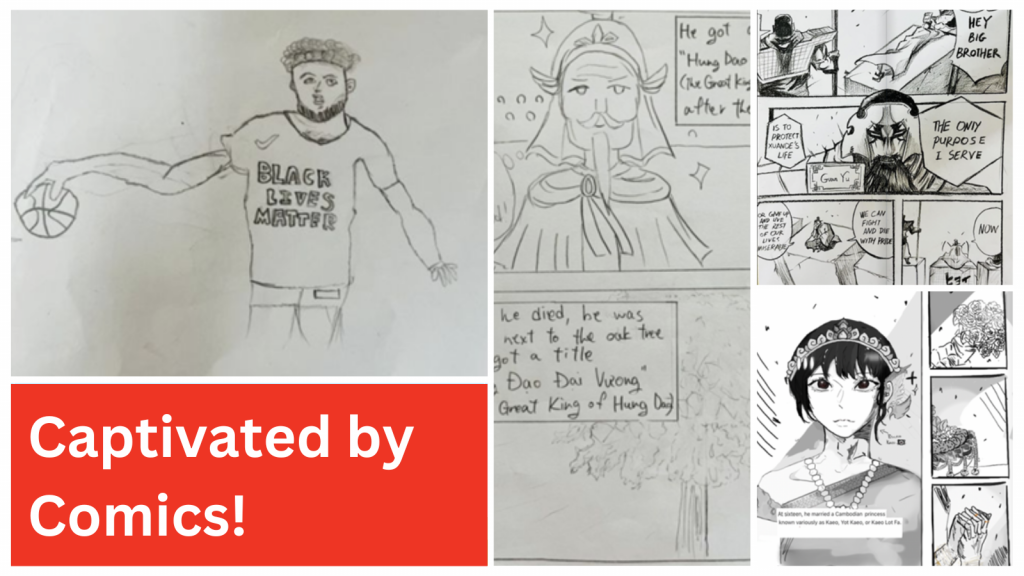

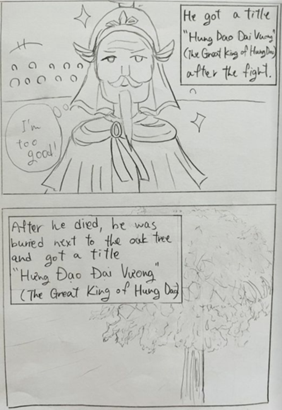

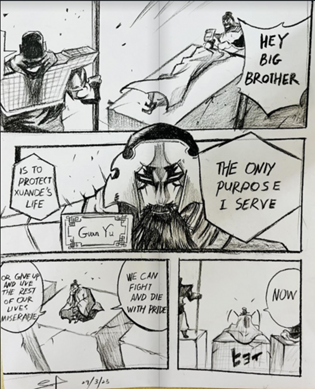

Last semester, Megan’s students embarked on an interdisciplinary unit called “Social Justice Heroes.” This unit combined elements of social studies and the arts as students were tasked with first researching a historical “social justice hero” from their home country and then creating a comic book to bring that person’s story to life.

Megan was inspired to create this unit after noticing that her students often seemed to be more engaged in the art classroom as compared to her social studies classroom. Students who could focus for ten minutes maximum in their social studies class were focusing for ninety minutes or more in the art classroom, even forgoing breaks.

Megan asked the art teacher why she thought this was the case and the art teacher said, “Students enjoy the process of creating art a lot more than they do creating traditional written work in school.” When Megan asked the art teacher if she thought comic books would be a good medium for capturing students’ attention, the teacher replied, “Students love to express themselves visually using different media. And students who are less inclined towards writing, in particular, could flourish in the comic book creation process.”

Indeed, during the six-week unit, the students were actively involved in the process of creating their comics. They studied mentor texts, researched their heroes, planned their stories, collaborated and sought feedback, drafted their comics, and revised their work. They analyzed a plot diagram and discussed the different elements a story needs to be exciting. They watched YouTube tutorials, such as the ones on this playlist created by Proko, to practice skills like drawing characters and showing emotion through movement.

The final products were read aloud to grade four students at the school. Having to prepare their comics to show to an authentic audience gave both purpose and meaning to the work. The students took pride in what they had created and were excited to share with others.

Conclusion

Comics can be a powerful tool to capture the attention of middle school students. They’re also fun! We hope that this article has provided you with some ways you might use comics in your own classroom. If you have not tried using comics before, don’t be afraid to take the risk and try it out. It’s ok to be a learner with your students. In fact, they often appreciate it when the teacher doesn’t have all the answers. For further exploration, we suggest a few resources:

- Marzano Research – How to Use Comic Books in the Classroom

- Teaching with Comics and Graphic Novels

- Graphic Novels and Comics in the Classroom

- Pop Culture Classroom

Megan Vosk and Jason DeHart are both members of the AMLE Teacher Leaders Committee.

Megan Vosk teaches MYP Individuals & Societies at Vientiane International School. She is also the chair of the AMLE teacher-leader committee. She can be reached on Twitter @megan_vosk.

Jason DeHart earned his PhD in Literacy Studies at the University of Tennessee, Knxville in 2019. DeHart has served as a middle school teacher, high school teacher, and assistant professor.