Imagine students wanting to improve their writing—just because!

What if students improved their writing because they wanted to, not just to get a good grade? What if their motivation to do better was fueled by teacher conferences and quick feedback?

That fantasy could be closer to reality than you ever imagined.

At Danville Middle School in Danville, Pennsylvania, our path to improved writing began with changes to our state-mandated assessments. When Pennsylvania’s Department of Education unpacked the text-dependent analysis (TDA) question, it sent an enormous ripple into the stress pond for both teachers and students.

Text-dependent analysis questions call on students to synthesize answers based on specific evidence within a reading passage and demonstrate their ability to interpret the meaning behind that evidence. Students must construct a well-written essay to demonstrate their analysis of the text rather than simply summarize the content.

We pushed our students and ourselves to master text analysis in writing, but after the first year, our results were mediocre at best. At worst, the students began to hate writing and we were all stressed out. Clearly, our plan needed work.

Working Together

Part of the frustration we felt stemmed from students’ inability to do what we asked of them. We expected our middle school students to analyze, yet we had not taught them the concept of analysis. For years, the push had been on comprehension, but it stopped short with the deeper literary analysis through writing.

Our initial throw-it-all-at-them-and-hope-for-the-best plan had proved unsuccessful for the majority of our students. So last year, we started with the basics, modeling our expectations and creating graphic organizers to help students map out the steps required for the reading analysis. We also included another key component: interdisciplinary collaboration.

When the language arts and social studies teachers began to discuss the TDA and its ramifications for all of us, the blurry line between content areas slowly vanished. We adopted the “divide and conquer” mentality.

Our first step as a team was to develop a common language. Students no longer needed to guess what this teacher wanted in an essay versus what the other teacher wanted. Our students heard a unified message about the importance of writing with an academic focus. We were on the same page. And so began what was in many ways a learning process for us all.

Baby Steps

We started slowly. The language arts team collaborated to write the first TDA of the year. We read three passages as a class, and teachers modeled how to construct strong introductory and body paragraphs. We presented students with the state grading rubric and evaluated state-released samples that we scored and discussed as a class. When they were able to analyze the work of others, students were closer to being able to recognize and emulate the components in their own writing.

Students typed their first TDA response and, with the convenience of Google Classroom and Chromebook technology, language arts teachers printed their essays without their names and distributed them with detailed scoring rubrics that focused students on the specific skills required in each paper.

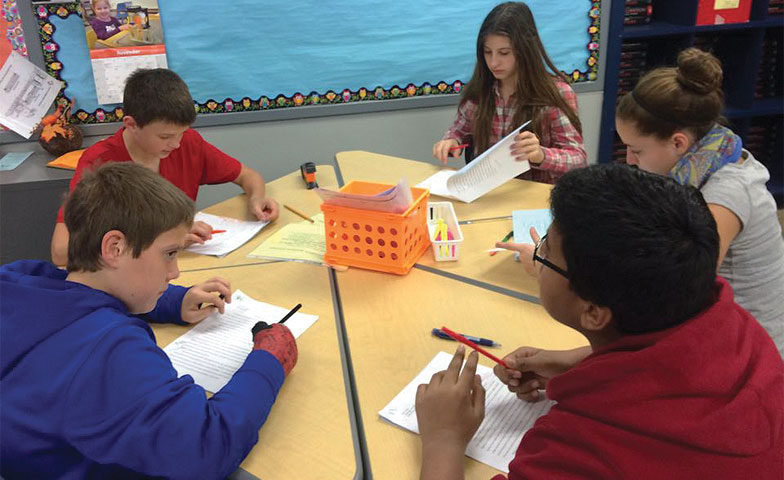

These essays were shared with groups of students wielding colored pens—perfect for positive reinforcement or gentle revision suggestions. For three days, students pored over their classmates’ work, focusing on specific aspects of the writing and comparing them to the state evaluation tools.

During this exercise, small groups were able to discuss their opinions, compare responses, and recognize both good and poor examples. More than one student remarked, “I have a new respect for what you do for a living, Mrs. Smith,” after muddling through a paper with typos and sentence structure issues.

When students got their original papers back, now covered in multi-colored comments from their peers, they set about revising them with renewed enthusiasm. Their only grades at this point were for class participation—a reward for a job well done when it came to wearing the editor’s hat.

Building Blocks

It was in social studies classes that students sank their teeth into their first “independent” TDA. By this time, our four-person social studies/language arts team had revamped the previous graphic organizer for writing and developed a student-friendly rubric that made expectations clearer for students and grading easy for teachers. The rubric also threw in a few tips for those students who struggled along the way:

- A checkmark system for “observable skills.” (Did your teacher see a thesis statement? Was a graphic organizer completed?)

- A column for identifying “skills to practice” in order to improve.

- The all-important ownership section where students complete the sentence, “On my next TDA I will…”

Along with the ownership piece, one of the most valuable aspects of this collaborative effort has to do with the one-on-one attention students receive after each TDA. It may seem impossible to get 100 student-teacher conferences done within a short time period (we work with an average one-week turnaround time for grading and conferencing), but somehow we make it happen. Part of that success comes from expertly managing class time; the other part calls for maximizing “free” time during the day like advisory and RTII classes where groups are smaller and students can use that time for revision as needed.

Key Ingredients to Success and Sanity

How can teachers fit “one more thing” into an already overflowing to-do list? We work together. We split the team of 100 students into two classes each, and we alternate who grades which classes after each TDA

so we can track all students’ progress.

Something miraculous happens to teachers when the daunting task of scoring 100 essays is cut in half. It’s like a rush of adrenaline. Suddenly, the marathon has become a half marathon, and we just scarfed up a box of energy bars. Sure, it’s still 50 essays, but the TDA rubric that’s student-friendly is also kind to teachers. It makes scoring essays much less painful. We use a system of checks:

- Thesis statement: That gets a circled “T” on the paper.

- Text-based support in the form of a quote: That gets a circled “Q.”

- Well-placed analysis: That gets a circled “A” (and sometimes even a few exclamation points depending on how excited or tired the grader has become).

We do very little, if any, line editing. As writers and teachers, and teachers of writing, it was difficult to train our brains to overlook glaring errors at first, but the reality of the state’s holistic scoring process dictates that teachers be more concerned with content and analysis than the finer details of perfectly placed commas. Also, students who are not strong writers don’t see their page saturated with purple ink, and therefore don’t get discouraged from continuing to improve their essays.

After we score the essays, we divide and conquer again to review TDA results with individual students. They are eager for our undivided attention and task-specific conversation. As teachers using the same language, graphic organizers, and expectations across the board, we are sure our students are well-versed in what we expect, striving to improve, and seeing the evidence in their scores.

With manageable goals, even the students who struggle the most are making strides without feeling overwhelmed. The key is baby steps. Through scaffolding, we target the small pieces—structure and solid thesis statement writing—before moving on to analysis. More advanced writers get a nudge toward strengthening transitions and varying word choice.

The Home Stretch

As a final push before test season was upon us, the students filled out a bar graph charting their progress on TDA writing for the year. They honed in on the areas where they continued to struggle, but they also celebrated their accomplishments—and there were many.

Whether the standardized test results prove that our strategy worked is almost irrelevant. We have witnessed the progress, celebrated individual milestones, and instilled strong writing skills and structure in our students.

Although we have scored their TDAs, we have not counted them as grades to include in their average. No one seems to ask, and no one seems to care.