Every day, millions of 10- to 15-year-old students walk through the doors of their middle schools with anticipation and great hopes for their future. Some will fall into leadership positions, but something so important should not be left to chance—or to the few.

Every student has the potential to be a leader, and their teachers and administrators have the responsibility to establish a school climate that nurtures their growth as self-sufficient, engaged citizens, and to develop their leadership skills.

Parma Middle School students present during a schoolwide assembly.

Social psychologist Martin Chemers defines leadership as “a process of social influence in which a person can enlist the aid and support of others in the accomplishment of a common task.” Isn’t that a skill we would like all our students to have? When students have the opportunity to lead, they become architects of their futures and change agents in their schools and communities.

Adults sometimes doubt the readiness of young adolescents to be leaders—or perhaps they are apprehensive about what will happen if they share the mantle of leadership with students. That concern ignores one of the key attributes of effective middle level schools according to AMLE’s This We Believe: Keys to Educating Young Adolescents: Effective middle schools empower students and provide them with the knowledge and skills to take control of their lives.

Providing all students with leadership opportunities helps them grow into responsible adults. If we want students to work in partnership with adults, we must give them the opportunities to develop leadership skills—skills that allow them to manage time, work as a team, set goals, solve problems, facilitate meetings, defend positions, and make effective presentations. In other words, we must help them develop effective life skills.

Anderson Williams, an educational consultant and co-founder of Zeumo Communications, works in the area of youth development. According to Williams, schools must deliberately provide opportunities for youth leadership.

Granite Falls students planned and organized a youth summit.

“Too often, we defer leadership to later grades or even to adulthood, and then ask people to be leaders, to make critical decisions, when they have never developed that skill,” he says. “While educators should help students practice making decisions at all levels, it is critical in the middle school years to start making some decisions with consequences. If we ever plan to ask students to lead, we must prepare them. If we don’t help them practice decision making, we are setting them up to fail when we do so.”

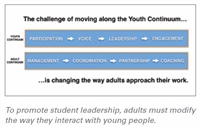

Williams created two resources that help identify the different stages in youth engagement/leadership and the adults’ supporting roles at each stage: Understanding the Continuum of Youth Involvement and Youth-Adult Continuum. The first shows youth development from participation to voice, leadership, and engagement. The second identifies the roles of adults as they support youth along the development continuum—roles that require the re-envisioning of adult–youth interactions. Visit the Forum for Youth Involvement at www.forumfyi.org for resources.

Youth Leadership in Action

Through Project UNIFY, Candice shows athletes there’s more to life than being bullied.

Special Olympics Project UNIFY® has been working with educators for the past seven years to create socially inclusive schools where all youth are provided opportunities to be leaders. In fact, Project UNIFY is built on the premise that the change process must start with young people and that students must have opportunities to take active, leading roles in their schools and communities.

As referenced in Project Unify’s A Framework for Socially Inclusive Schools, when youth leadership is central to the school’s culture, the following attributes are apparent:

- Opportunities for credible relationships exist among students, teachers, and administrators. All young people, regardless of ability, are given a voice to make meaningful changes in their classrooms, schools, and communities.

- All youth are given opportunities to execute their decisions and be leaders and agents of change.

- Students co-develop, maintain, and are accountable for inclusive climates in their classrooms and schools.

- Adults model the attitudes, skills, and efforts required of leadership and provide opportunities

- to empower youth to be leaders.

These attributes become a reality when students serve on inclusive youth committees or clubs; collaborate as club officers; plan school assemblies; and serve as team leaders on Unified Sports teams. The students identify a need for equity in their schools and work to make it a reality, advocating for others—and, thus, advocating for themselves.

That’s the philosophy behind inclusive youth leadership, but what about the reality? Bill Schreiber, principal of Granite Falls Middle School in Caldwell, North Carolina, is a strong advocate of middle level students taking on leadership roles, and he believes that Project UNIFY has provided concrete avenues for that to occur.

Granite Falls students show support for Project UNIFY athletes.

“Youth leadership opportunities provided through Special Olympics and Project UNIFY allow our students to, as [leadership expert] John Maxwell said, become young leaders ‘who know the way, go the way, and show the way’,” Schreiber says. “Students in our program set the standard for others to emulate. That starts in the Project UNIFY program where they develop the ability to advocate for those less fortunate and in need of a friend.”

Beyond the School

Leadership opportunities go beyond school when students work with Project UNIFY. In each state, students have the opportunity to participate in Youth Activation Committees where they design and implement summits and activities on the state level, which are then redirected back to their schools and communities.

Barbara Oswald, director of youth initiatives for Special Olympics South Carolina, shares the power of youth leadership—particularly intergenerational leadership.

“Young leaders, with and without intellectual disabilities, have taken the reins on initiatives and programming at the local and state levels, inevitably changing the way those initiatives and programs look,” she says. “Youth leaders provide us with tools and strategies for better engaging youth at the grassroots level. They provide us a new vision for what Special Olympics can and will look like in the future…. The younger generation of leaders can pave the way for these new societal ‘norms,’ while the opportunity to serve as a leader through the Special Olympics Unified Movement provides an opportunity for young leaders to develop the soft skills that can make them successful leaders in their future.”

And then, there’s the altruistic impact of youth engagement and leadership when working in an area of social justice. Candice, an eighth grader at Carolina Springs Middle School in Lexington, South Carolina, says, “Helping with Project UNIFY has made me become a better leader by helping the athletes learn, showing them there’s more to life than getting bullied. Showing them someone loves them and wants to be their friend. When people call me a leader it touches my heart! When I get called a leader it makes me feel I can accomplish anything. Being with Project UNIFY opens me up where I can see the world without blinders. Project UNIFY has changed the way I look at the world.”

Youth leadership is powerful, and it’s our responsibility to find avenues for every student to develop as a leader. When we further engage in an intergenerational way, the benefits are compounded for students, adults, and the school community.

Partner’s Clubs: The Student Perspective

| A Partner’s Club is a club for students with and without intellectual disabilities who come together for sports, games, community service, school events, and to have fun (www.specialolympics.org/Sections/What_We_Do/Project_Unify/Project_Unify.aspx).

Patricia Shishido, counselor at Parma Middle School in Parma, Idaho, works with an inclusive group of students in their Partner’s Club. She shares the following thoughts from her students. “It makes me feel really good to be a leader of Project UNIFY Partner’s Club… because it makes me feel that people think I have hidden talents inside. It means a lot to me because I can help my school and people that need help. For example, I can help try to set people on the right path. I feel that I have made a difference. I have had many people come up to me and tell me I made a difference in their lives.” —Ariel, grade 6 “Being a leader means a lot to me because I am a leader in everything I do. I feel I have made a difference. The thing I enjoy most about being a leader is knowing that I am helping someone whether raising money or going to a Partner’s Club event…. We have also organized some great Partner’s Club activities. That is why I love being in Partner’s Club and being a leader.” —Brandie, grade 7 “Being a member of Partner’s Club is so fun, and it brings good feelings to me. The thought of helping someone is amazing. The moment we put a smile on their faces is great. It is important that everyone has a friend who is there for them.”—Colby, grade 8 “I try to do my best as the secretary of the Parma Middle School Partner’s Club. This club has changed me over a period of time because I am surrounded by so many positive people. Partner’s Club is the most supportive group I have ever joined…. We encourage everyone to be respectful, helpful, and to be happy.” |

Betty Edwards is the former executive director of the Association for Middle Level Education and the current chair of the Special Olympics Project UNIFY National Education Leaders Network.

bedwardsk@aol.com

Published in AMLE Magazine, October 2015.